The Chinese treatment of the Uyghur minority in Xinjiang puts the EU’s China policy into question.

The Chinese government has been accused of repressing the Muslim Uyghur minority in the Xinjiang region, and has been the subject of numerous investigations. These have revealed, among other things, forced sterilisation, rape and forced labour. Estimates are that hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs were subjected to mistreatment. Images were published of men and women being locked up, blindfolded, hands tied and heads shaved, under the surveillance of Chinese authorities, armed with assault rifles and not hesitating to shoot.

According to reports, the measures by the Chinese authorities started in July 2009, when ethnic riots broke out in the form of street clashes in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, between Uyghurs and Han Chinese, the majority ethnic group in China. Terrorist attacks by Uyghurs followed in 2013 and 2014, particularly in Beijing. China’s interest in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region lies in its strategic location for Beijing, both in terms of geography and natural resources. Occupying one-sixth of China’s surface area, the Xinjiang region allows for the transit of goods and cultural exchanges due to its location on the ancient Silk Road. In addition, the region is rich in coal, natural gas and oil.

The threat of terrorism was met with a harsh repression of the population. Speaking Uyghur, practising Islam or following local traditions is often punishable by torture and imprisonment. Investigations also established the existence of Chinese government facial recognition software which targets Uyghurs in particular. The Chinese authorities have strengthened the military apparatus in the region and reportedly seek the erasure of Uyghur identity.

European and international sanctions

In July 2020, 22 countries (including France and Germany) wrote a letter to the United Nations to denounce the situation. The United States imposed sanctions against several Chinese companies for their purported participation in the persecution of the Uyghurs, as well as against Chinese leaders.

The European Union, for its part, imposed sanctions against four Chinese officials and one entity linked to the authoritarian crackdown in Xinjiang in March 2021. These measures prohibit the individuals from travelling to the EU and freeze any assets held within the EU.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Ceg0-lDL7Os/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

On 16 November 2021, official Chinese documents detailing this repressive policy were published by the “New York Times”. These documents include the demand for the establishment of a dictatorship, as well as certain instructions concerning the explanations given to the families of the detainees. Thus, it is possible to find certain speeches such as “contamination by the virus of extremism which must be cured before the disease degenerates”.

In May 2022, the chairman of the European Parliament’s delegation for relations with China and former European Green Party Chairman Reinhard Bütikofer, called for new sanctions against China. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and the European Parliament have called for a ban on goods imported from China that originate from the forced labour of Uighurs in Xinjiang by September, despite the reluctance of the European Trade Directorate.

Xinjiang Police Files

In mid-May 2022, new photos were released showing, according to European media reports, prisoners’ faces and instructions and speeches such as “any prisoner who tries to escape, even by a few steps, must be shot”. These “Xinjiang Files” contain thousands of Chinese police documents. They include archives preserved since 2000, which are particularly interesting between 2017 and 2018, when the Uyghur internment camps were set up.

After the disclosure of these documents, the United States expressed their indignation, while on the European side, the head of German diplomacy Annalena Baerbock asked her Chinese counterpart Wang Yi for “clarifications” on the documents deemed “shocking”. The French government had already rejected the term “genocide” earlier this year when the French National Assembly adopted a resolution officially recognising the “violence perpetrated by the authorities of the People’s Republic of China against the Uyghurs as crimes against humanity and genocide” and “condemning” them.

On 22 March 2021, the European Union sanctioned China for the first time since 1989. The sanctions were imposed on four Chinese officials, relating to a visa ban and an asset freeze in the EU, as well as on one Chinese entity. The EU accuses these individuals of “serious human rights violations”, “arbitrary detentions and degrading treatment of Uyghurs”, and “systematic infringements of their religious freedom”. These EU sanctions are possible since the establishment in December 2020 of a mechanism allowing Europeans to punish those involved in human rights violations. In addition, the European Parliament has been supportive of these sanctions.

China’s response to sanctions

The Chinese government strongly denied the accusations levelled against it. The Chinese Communist Party explained in 2018 that people had been put in “vocational training centers” to “fight terrorism, promote social stability and educate and transform” the Uyghur minority to provide them with “employment opportunities”. The detention facilities are officially called “political reeducation camps”. The Chinese regime has reportedly not hesitated to use the word “concentration camp” in exchanges between leaders.

Following these accusations, Beijing fought back by accusing the European Union of interference. The Chinese Foreign Ministry also called on the EU to “correct its mistake” and not to interfere in Chinese internal affairs. The Chinese government denounced “lies” and intentional “disinformation”. In turn, it takes sanctions against four European entities and ten European officials, including Bütikofer and French MEP Raphaël Glucksmann, banning them from mainland China and from doing business in China. EU diplomatic chief Josep Borrell responded to the imposition of the sanctions by saying that they “will not change the EU’s determination to defend human rights”. He also described the Chinese sanctions as “regrettable” and “unacceptable”. Shortly afterwards, the United States also imposed sanctions on the Chinese government, calling the Chinese repression “genocide”.

The balance between sanctions, co-dependence and trade is a perilous one for the European Union. Chinese counter-sanctions risk going beyond the diplomatic sphere and calling into question certain trade agreements, notably the “Global Agreement on Investment”. This agreement was put on hold by the European Parliament in 2021 following the degradation of relations between Brussels and Beijing.

Controversial visit to Xinjiang by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights

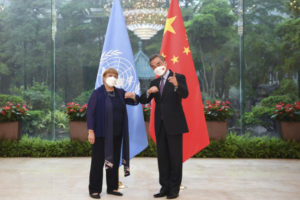

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet visited China on 22 May 2022, in the context of the “Xinjiang Police Files”, but assured that her visit was in no way a UN “investigation” into the fate of the Uyghurs. Bachelet said she had simply urged Beijing to stop “arbitrary” measures against the Uyghurs.

The visit was severely criticised. Many NGOs expressed outrage at Bachelet’s failure to publish any detailed report and noted that the visit was a “missed opportunity” to highlight human rights in China. They also denounced a loss of credibility of the UN on the subject.

Catherine Colonna, French Minister of Europe and Foreign Affairs, followed by her Dutch counterpart Wopke Hoekstra, called for full transparency on the situation in Xinjiang and for Bachelet to be given unlimited access to the region. The US, on the other hand, expressed doubts about the transparency of the visit and the absence of interference in the human rights assessment of the region. Germany took a more pro-active approach, loudly condemning the oppression and developing a specific policy towards China geared towards the protection of human rights. However, it is still unclear what practical consequences Berlin will undertake in this regard.

Double standards?

Already during the 2014 so-called Umbrella Revolution, Hong Kong found itself on the frontline between democracy and dictatorship. In several other cases, such as the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan or the revelation of human rights violations by China, the European Union issued its recommendations without much effect. However, as was shown following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the EU is capable of unity. For example, it agreed to provide hundreds of millions of euros in aid to finance the sending of arms to Ukrainian forces. In addition, it has imposed financial, economic and diplomatic sanctions on Russia.

When it comes to China, however, Europe has so far not shown the same resolve. This may be due to the fact that Chinese firms invest almost five times as much in Europe than Europeans do in China. Until now, EU member states have lobbied for the idea of a greater opening of the Chinese economy forEuropean companies, goods and investments. In 2021, China was the EU’s third largest partner for exports of goods and the EU’s largest partner for imports of goods. Apart from that, relations have intensified in the fields of research, development and technology.

Notwithstanding, there have been concerns, in particular over security conditions, for some time now, including over data protection or the risk of espionage. Engaging China on the digital ethics has posed a challenge for the EU. Beijing’s relationship with the European Union is of crucial importance despite the recent accusations over the treatment of Uyghurs.

If one looks at the European Union’s policy towards Russia, one will notice a stark difference to its policy towards China. Indeed, from the very first days of Russia’s war against Ukraine, the European Union has provided 450 million euros in financial aid to fund the shipment of weapons to Ukrainian forces. In addition, it imposed financial, economic and diplomatic sanctions on Russia. Some restrictive measures had already been taken against Russia prior to the Ukraine invasion in February, such as during the illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014.

All these measures confirmed the adage that “the European Union only advances in crises” (an adage that had already been consolidated with the Covid-19 crisis). As a result, some expressed the view that Europe was finally giving itself the means to act as a geopolitical power. Its attitude towards China, especially when it comes to the human rights situation there, will be critical in determining whether or not the EU can be a credible and powerful actor on the international stage.

Author : Hélorie Duval and Emma Leblond